VII. Luigi Caccia Dominioni

The Ambrosianeum Chair from 1955 (left) and the Luis Chair from 2003

Luigi Caccia Dominioni — Born in Milan, Italy, 1913

The beauty of form is either a digression or a clarification. In the latter case — clarification — time or collective use is the shaper of form, as in the way a spoon or any quotidian object is morphed by broad utility through generations. The former case, the digressive, is when an individual journeys into an exclusive focus on the shape of a particular thing; this is the singular task of designers, generally speaking. This is true for the deceptive simplicity of Dieter Rams as well as the material arabesques of Ettore Sottsass. To be clear, contrary to popular opinion, a designer doesn’t clarify, she/he explores. An individual can’t possibly control the unforeseen and logistical, like the cosmic economy of collectivity, so it is giving shape to the mystery of memory and preference that really informs a designer’s quarry.

In light of the above lines, the work of Luigi Caccia Dominioni is an impeccable example of what a single designer can achieve. His 70-plus years of work have yielded buildings and objects of a deep sensitivity.

Dominioni’s 1953 Monachella floor lamp for Azucena.

Dominioni is an architect and a designer. At university he studied under Luigi Moretti (a first-wave Italian modernist), which seems to have been a fairly influential tutelage, as Dominioni’s architectural work has consistently been in close dialogue with this first phase of modernism. His professional life started successfully, designing objects and interiors with the Castiglioni brothers (Achille, Livio and Pier Giacomo). He is often quoted as saying that a good building is designed from the inside out, and this idea was surely the catalyst for Dominioni’s 1947 opening of Azucena, a design firm focusing on furniture and objects. From then on, Dominioni was a cornerstone of the post-war generation of Italian architects, alongside Franco Albini, Ico Parisi, Ignacio Gardella, Osvaldo Borsani, Angelo Mangiarotti and Carlo Mollino.

When looking at Dominioni’s designs, it is important to keep in mind that European homes, unlike those in the U.S., are often older, having ornamental notes in the keys of different eras (at times classical, sometimes even ancient). And, even if a particular building is totally new, the street on which it rests typically presents an array of historical perspectives. American designers working in parallel with Dominioni (George Nelson, Charles Eames, etc.) were less confined and were often designing toward unbuilt, forward-looking vistas. The shapes of much midcentury modernist Italian furniture, due to said architectural constraints, have a modern feel, but with accents more inclusive of a multitude of situations; whereas much American furniture can feel of the time. Dominioni's Monachella floor lamp (1953), Ambrosianeum chair (1955), Boccia sconce (1967) and Pipistrello desk (1998) speak to this versatility amazingly well.

The Pipistrello desk for Azucena (1998)

The Boccia sconce (1967) and the Porta Dipinta table lamp (2002), both for Azucena

There is an element of Dominioni’s work which separates him from all his peers, and which brings us back to the first inquiry of this essay: design and the expression of beauty. In an interview, Dominioni pointed to himself as “urban,” a word he explained as connecting his architecture and design to function, thinking of the city as a place of pure utility. Initially, this statement may seem to undermine what I originally said about him being digressive more than functionally inclined — but invoking functionality is a conceit of most architects and designers; it is expected and understandable. But the practical pursuit in good design is not the same as that of, say, an engineer of fluid dynamics; as ventured earlier, it is more mysterious, almost like the quality of being compelling. To put it another way: a good designer is not expressly working to design a chair around the problem of back fatigue, so that an employer can maximize working hours, but to design a chair as to confront our sense of Appearances. Looking at Dominioni’s work I don’t feel that it is correct, or tasteful, or intelligent, or even expressive. I see something like soft vortexes of examination — zones or dimensions of matter where potent focus has been applied. All of Dominioni’s work functions well as furniture, as interiors, or what have you—but it is his clear commitment to mastering gracefulness that sets his work apart.

Dominioni interiors from 1953, with his Imbuto floor lamp pictured at right

The Bicolore bed for Azucena (1989)

Dominioni’s 1958 Catalina chair and his 1962 Mikado table lamp, both for Azucena

The Sant’ambrogio sofa for Azucena (1981)

Left: the Nonaro Chair for Azucena (1962). Right: the CDO chair for L’Abbate

The Bordighera table for Azucena (1980)

The Fasce Cromate sofa (1963) and the Sciabola desk (1979), both for Azucena

The Panchina bed for Azucena (1960)

Dominioni interiors

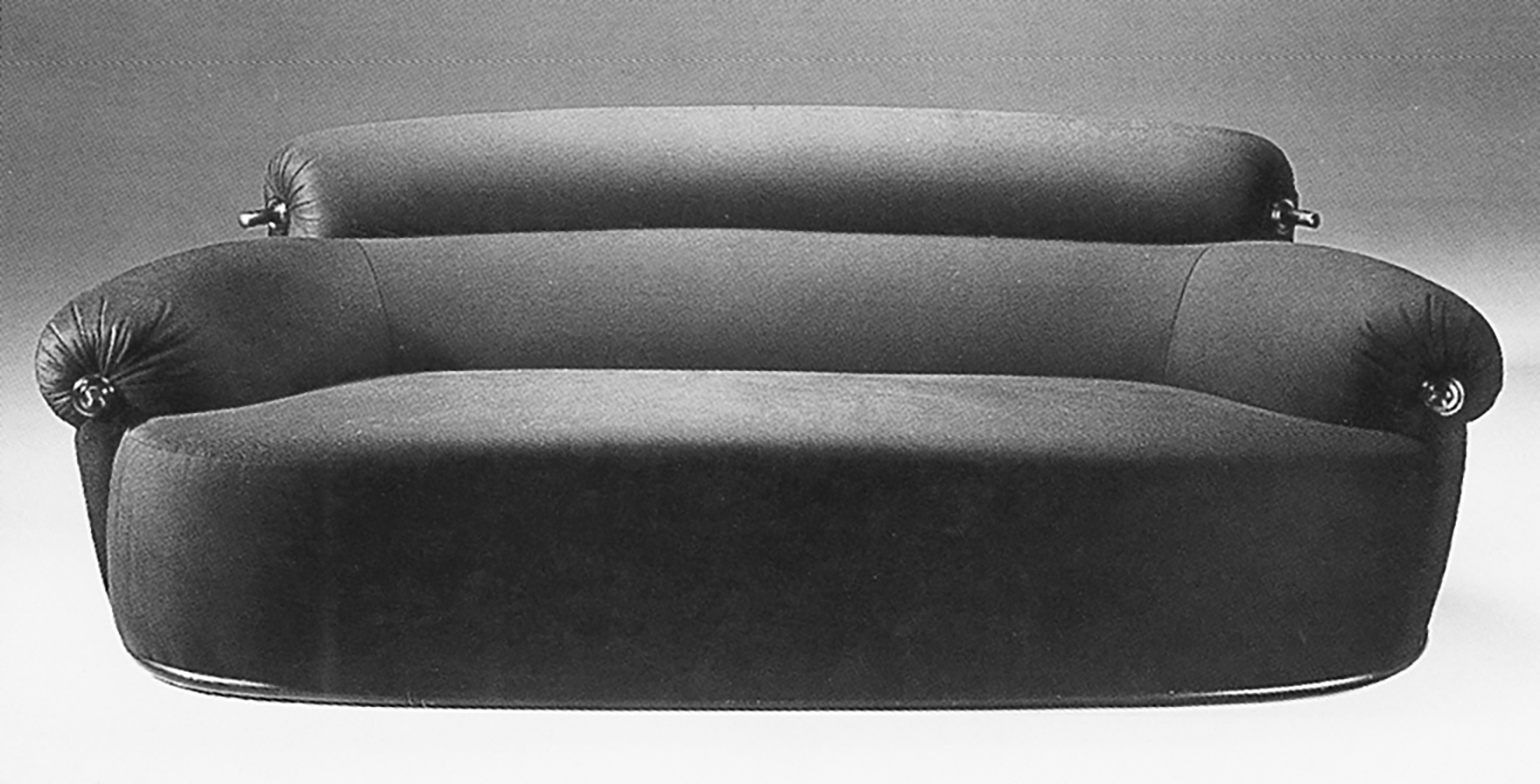

The Toro sofa for Azucena (1979)

— AQQ